With just over two months to the world’s biggest sporting event, the World Cup, all eyes have turned to Brazil. But for a country often pictured as a racial paradise, one thing has long eluded the nation of almost 200 million: business ownership more representative of its ethnic diversity.

The South American country has the second biggest black population in the world, after Nigeria, but white Brazilians continue to outnumber black (including mixed-race) business owners – many of them descendants of the four million slaves brought to Brazil between the 16th and late 19th century. Now, this looks set to change.

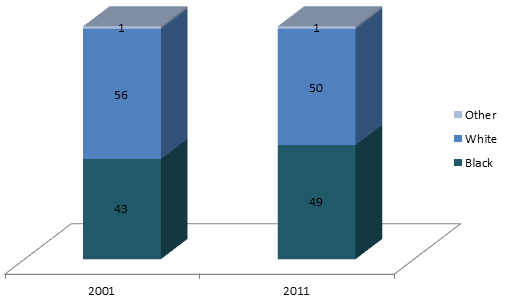

A report published in September last year by Brazil’s small business agency Sebrae, Os donos de negócios no Brasil: Análise por raça/cor (Brazilian business owners: an analysis by race), revealed that black business owners made up 49% of all business owners in 2011 – up from 43% in 2001. The group makes up 52% of the population.

Proportionately the percentage of white business owners shrank from 56% to 50% over the same period, with Asian and indigenous people accounting for the remaining one percent. Yet white Brazilians still make up a disproportionately higher number of business owners, as they account for 46% of the population.

The number of black business owners grew by 29% between 2001 and 2011 – from 8.6 million to 11 million – while the number of white entrepreneurs increased by just one percent (from 11.4 million to 11.5 million) over the same period.

Fuelling the change has been a stronger and more stable economy and social policies, which helped the incomes of black Brazilians increase by 123% between 2000 and 2012 – five times faster than the rest of the population, according to a report by Globo newspaper in 2012.

Still not equal

Yet despite their significant increase in numbers, black business business owners still bring in on average less than half the income of their white counterparts.

They also have proportionately less years of education, are younger (with an average age of 42, compared to 45 years for white owners), work less hours per week (39 hours, compared to 42 hours for white owners), and have less access to resources like telephones and IT.

Low job impact

Most businesses owned by black Brazilians continue to be very small – just eight percent employ more than the owners themselves, compared to 19% of white-owned firms.

A higher percentage are involved in sectors where manual labor or low skills dominate – such as construction, agriculture, street hawking, bars, hairdressers, and small restaurants.

But the low performance of black-owned firms is not unique to Brazil alone.

In South Africa where black people (African black, Indian, and mixed-race people) account for 91% of the population and make up 92% of South Africa’s 5.6 million business owners, according to the Finscope 2010 Small Business Survey, just 29% employ anyone other than the owner. This is against 38% of white-owned firms that employ more than the owner.

For black African business owners this figure drops to 27%.

In South Africa during apartheid, black African people were effectively banned from running and owning a business. The regime’s education for black people was abysmal, while many were made to see themselves as second-class citizens. This has created not only physical barriers such as access to finance, business skills, and networks but also physiological barriers that still linger.

Poor quality education, low savings

In Brazil, black families, with lower incomes, have limited opportunities. Even among Brazilians with 12 years or more of schooling, whites still earn 32% more than black Brazilians, according to publisher Abril’s 2014 almanac – many by benefiting from networks and access to better universities.

In the US many African Americans have benefited from affirmative action policies in place since the 1960s, yet the group remains under-represented in business ownership – just seven percent of business owners are African American, although they make up 13% of the population.

Added to this white-owned businesses generate sales over six times higher than their black counterparts ($490,000 compared to $72,000 a year for the latter).

In a large part, experts cite the lack of personal wealth among African Americans. Things are unlikely to improve any time soon, particularly as African Americans were among the hardest hit by the foreclosure of mortgages in the 2008 crisis.

Malay challenge

It’s not just a problem facing black entrepreneurs. In Malaysia – where Malays and indigenous Malays (together referred to as Bumiputeras) make up 60% of the population, figures from SME Corp, the Malaysian government’s small business support organization show that just 37.4% or 205 000 of Malaysia’s firms are Bumiputera-owned.

Though Malaysia’s New Economic Policy (NEP) instituted in 1970 and its subsequent policies, including university quotas, may have had some success in boosting the share capital of Malays, it has also fuelled rent-seeking behavior by Malay entrepreneurs.

All kinds of theories have been advanced as to why so few Bumiputeras are business owners, with the country’s one-time prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, often dipping into the argument himself. Meanwhile Indian and Chinese emigrants – many with experience in business and strong networks with the business class in both their adopted country and in their homelands – have leaped ahead.

Some believe more sophisticated Malay entrepreneurs are now emerging following the help of state agencies and funds like the Bumiputera SMEs High Performance Programme in which the government aims to help 1 100 Malay companies grow their business regionally.

Policy problem

Specific programs and policies might help to open up more opportunities for marginalized groups, but they also have the potential to distort the market and create new problems.

In South Africa, the country’s Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) policy has benefited many black-owned businesses – not just well-connected and well-resourced black entrepreneurs – but it has also fuelled rent-seeking behavior and acted as a barrier against true risk-taking entrepreneurship.

For many, it is easier to take equity in larger white-owned firms than to start their firm from scratch – particularly given the country’s high failure rate. Like this, too many black business people have become dependent on others.

Added to this because of affirmative action policies many well-educated and well-connected black professionals can command top salaries, leaving many to remain in management positions at large companies, rather than start up their firms. Like this, it’s often the desperate and under-resourced that start up, which often only increases the chance of failure.

If more black entrepreneurs and those from other marginalized groups are to be fostered what is needed is better education for all – rich and poor and one without a hefty price tag attached to it. The society also needs to celebrate those entrepreneurs from marginalized groups that have succeeded. Here media and support organisations can play a critical role.

In the end, any policy will always be a gamble. Creating equal business ownership for all might amount to a socialistic pursuit that has more chance of failure than success. What is rather needed are equal opportunities for all. People from marginalized groups must be able to get a better start in life. It means building better schools, hospitals, and roads, increasing internet line coverage, training better teachers and doctors, and opening the internet to all.

Black Business in Brazil: Current Progress

Still, over the past couple of years, the face of black entrepreneurship in Brazil has assumed a change that reflects transformations underway in society as well as in the business arena. Historic disadvantages notwithstanding, increasingly inventive, resilient, and buoyed by an emerging ecosystem, Black entrepreneurs in Brazil are confidently forging their own economic space.

A great deal of centrality to this shift is the emergence of digital platforms, including apps like Whatsgb, and social media, which have democratized access to markets and resources today. Black business owners simply use the same tools to access a wider market, be able to showcase their products and build communities that would revolve around their brands. The empowerment that comes from this digital world is quite significant in a country whose traditional routes concerning business success have all too often been curtailed because of massive inequalities.

It also recognizes the importance and surge in buying from companies owned by previously under-represented groups, like black Brazilians. This fast-emerging sentiment that consumers are expressing is not only one that is of moral importance, but it is also transforming into a good business one; yet more evidence of a sweeping view in many quarters that entrepreneurship must be more inclusive and diverse.

The government and non-profit sectors have not been left behind in supporting black entrepreneurs, as most of these have increasingly offered programs that afford financial aid, mentorship, and training that give a solution to some of the existing limitations of entry for black business owners.

Solidarity and community are building among the entrepreneurs of blacks in Brazil. They are forming networks or collectives in which to exchange knowledge and gather their resources. This new feeling of togetherness transcends simple business contacts and reaches out to provide a sense of belonging as well as collective empowerment against societal challenges.

However, the positive trend notwithstanding, it is hardly a rosy situation. It is because of this that the blacks will continue to grossly outdo their counterparts by several percentage points in the area of income and education disparities, further choking the growth potential for black entrepreneurs. Such efforts require constant dedication from all sectors towards establishing a fair playing field.

Hi, I’m Sophie. As a digital creator and avid enthusiast in Business, Marketing, Finance, Tech, and News, I’m dedicated to delivering rich and engaging insights.

If you’re curious or have thoughts to share, let’s connect!

Contact: sophiekotecki@gmail.com